A Relativistic Game of Frontiers

A historical dive into "zero-sum" contexts, "non-zero-sum" frontiers, and their relativity.

Bird's Eye View

This is essay 2 of 4 essays for 1729 Writers Cohort #2. 1729 Writers is a group that writes to build on ideas related to Balaji Srinivasan’s new book The Network State, which can be ordered here. This post is purely academic in nature, and it does not constitute any formal political, scientific, legal, financial, social, religious, or ethical advocacy. For earlier posts and musings, please visit whatifwhatif.substack.com.

In a nutshell, this essay will make an attempt to connect lessons in history with theories in science. Specifically, it deep dives into the phenomena of '“zero-sum” contexts and “non-zero-sum” frontiers through a series of historical case studies — and in the end it synthesizes tie-ins with theories of Special Relativity and General Relativity. Let's dig in!

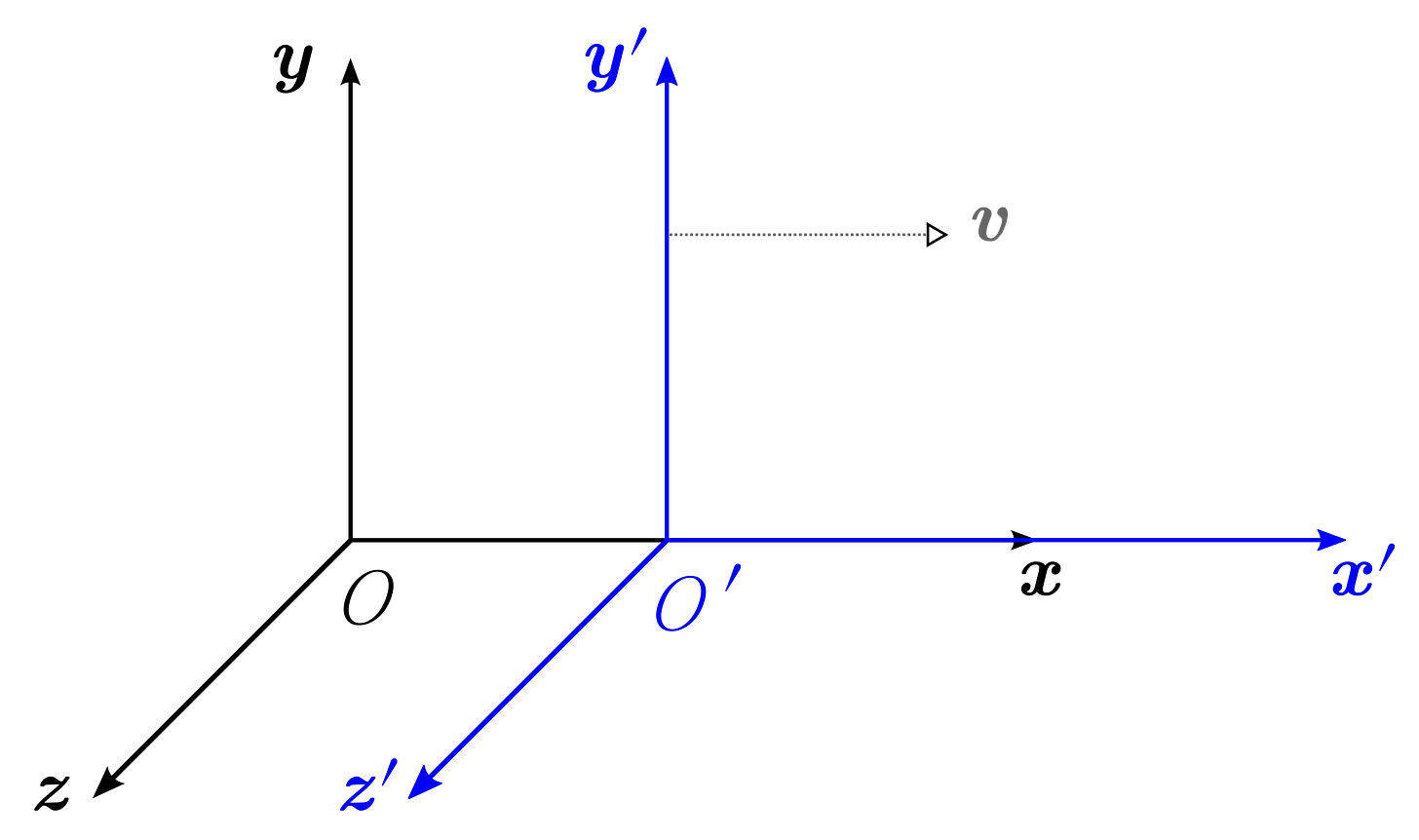

Physical and Digital Frontiers with Relativity (Source: Adapted from Mysid's Spacetime Lattice. Under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License)

Introduction

Through a series of no-punches-withheld discussions, Balaji Srinivasan's The Network State explores how we have arrived at the world of 2022, where we may be headed next, and what we can do to create new futures characterized by opening of new non-zero sum frontiers in the form of network states. In short, in a world headlined by a possible Second American Civil War and a possible Second Cold War, the Internet as a “digital frontier” could give hundreds of millions an alternative paradigm out of seeming impasse and “zero-sum” competitions. The concept of a "digital frontier”, or a "digital terra incognita," is further explored in the Frontier Thesis, which Balaji writes about here.

This essay subsequently builds on ideas of “non-zero-sum” frontiers and deep dives through exercises in history (wiki links to select names and terms are shared so that readers can read more), by specifically delving into three sets of examples of conflict and resolution (or lack of):

The Ideological Fragmentation Cases: Positive and negative examples in context of competing ideological factions.

The National Rivalry Cases: Positive and negative examples in context of intense rivalry between winning and losing nation state powers.

The Dynasty and Khanate Cases: Positive and negative examples in context of kings and khans.

At the end, we will extrapolate some further observations on frontiers and attempt to connect these observations to the theories of Special Relativity and General Relativity. Sometimes, insights into history and theories of nature could align.

1 - Competing Ideological Factions

The most common historical examples of frontiers appeared in contexts of ideological fragmentation and competition. Balaji has talked extensively about The Thirty Years’ War as a prime example of extreme divisions and violent balkanization (those interested are welcome to listen to Tim Ferris’ interview with Balaji here), as well as how the settlement of the New World gave breathes of fresh air to groups previously engaged in intense struggles. Hence, the first set of cases are not original, for I merely expand upon them.

Thirty Years’ War

The Thirty Years’ War constituted a series of conflicts from 1618 to 1648, involved more than a dozen nations and even more Germany principalities, and resulted in the devastation of the German heartland. There are many books and documentaries on specifics of the conflicts, so I won't go into details, but one could argue that the Thirty Years’ War was a case of ideological fragmentation and “zero-sum” without frontier exit points. The German heartland of 17th century was largely landlocked between great powers: France to the West, Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to the East (yes, Poland was a great power in 1618), the Habsburg Empire to the South, and the Sweden to the North (and yes, Sweden under Gustavus Adolphus was an emergent power in the 17th Century). When fights broke out between members of the Protestant Union and Catholic League, pitting different factions within the Holy Roman Empire against one another, the conflicts snowballed into larger and even larger zero-sum scales. Villages were burned, peasants became landless, and millions perished by the time the Treaty of Westphalia came around.

Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden Charging During Thirty Years’ War. (Source: Under Public Domain)

England and the Americas

By contrast, the religious and ideological conflicts of 17th Century England, though violent, found exit points in new frontiers of the New World. In response to the ‘Eleven Years of Tyranny’ under King Charles I, thousands of dissenting Puritans sought freedom and launched the Great Migration, which established frontier colonies in the form of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Connecticut Colony, the New Haven Colony, as well as other outposts in the Caribbean. Though some of the Puritans returned to England following King Charles’ decapitation, a good number stayed in the New World, unbothered by the trials and tribulations in the old continent. The exits were clear and parallel settlements were built.

Puritans Going to Church by George Henry Boughton. (Source: Under Public Domain)

2 - Intense National Rivalries

The next set of historical examples stem from the Franco-German conflicts of the 18th and 19th centuries. We will examine how the existence of frontiers softened the blow for the losing side and sustained peace for the winning side, while zero-sum existential struggles between great powers doomed entire generations to revenge cycles.

The Congress System

Following Napoleon's defeat and the 1814 Treaty of Paris, the main European powers, under the Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich, convened in a series of discussions collectively known as The Congress of Vienna, which outlined the balance between great powers and maintenance of peace on the European continent. Subsequently, more congresses — collectively known as the Congress System — were held, and Britain, Austria, Prussia, Russia, and France hammered out their differences.

Portrait of Metternich by Thomas Lawrence. (Source: Under Public Domain)

An interesting development within the Congress System was European powers’ mutual support of each other's imperialism and colonialism — as a method to diffuse conflict and shift focus outward onto new frontiers. The multilateral engagements and continental stability between great European powers went hand in hand with colonial expansionism and conquest. A specific case would be France's colonization of Algiers in the 1830s, which received the approval of its erstwhile European rivals, during the Napoleonic Wars. Restrained on the European continent, France turned its attentions outward to new frontiers in North Africa (here, the concept of frontier is applied in France's context, as it was unfortunate for Algerians who called it home). Austria and Prussia welcomed France's move, for it meant that future Napoleons would busy themselves near the Saharan desert as opposed to in the Rhine. The intense zero-sum rivalries during the Napoleonic Wars gave way to an open race in the African continent and beyond (those interested in delving more into the Congress System's link to colonialism can read this essay).

Versailles Redux

By the time of the Franco-German War and World War I, all of the known world had been colonized many times over, and what were previously geographical frontiers all fell under the sphere of influence of a great power. The “non-zero-sum” gateways built through the Congress System gave way to intense Darwinian zero-sum competition and rivalry. Upon France's defeat by the newly formed Empire of Germany and signing of the 1871 Treaty of Versailles, which ceded Alsace and Lorraine to Germany, a wave of revanchism or revenge would ride the French Republic and its new generations into the early 20th Century and into World War I.

Proclamation of the German Empire (at Versailles), by Anton Alexander von Werner (Source: Under Public Domain)

Upon Germany's defeat in World War I, the tables reversed at Versailles, and through the subsequent Treaty of Versailles, the French exacted revenge by advancing a series of terms that chopped off 65,000 square kilometers of German territory and demanded exorbitant reparations. It was Germany's turn to be humiliated and to ride revanchism toward its remilitarization in the 1930s under the Third Reich. The cycle repeated under another generation, and in June of 1942, the Wehrmacht entered Versailles again.

3 - Dynasty and Khanate

The final set of historical examples shift eastward. We will delve into how non-zero-sum frontiers helped dynasties sustain growth and momentum, while zero-sum thinking forced powerful houses to split.

Shang and Zhou Dynasties

Most people today think of ancient China as inhabiting a continuum of land with nearly static borders well defined by the Great Wall, the Gobi Desert, the Tarim Basin, and the seas to the east and west. However, that was not always the case for at least one third of its history. Chinese history for much of the 2nd and 1st millennia B.C. during the Shang dynasty (approximately 16th century B.C. to 11th century B.C.) and Zhou dynasty (11th century B.C. to 256 B.C.) was characterized by aggressive frontier expansion and colonization.

The King of Zhou famously assigned dukes and counts whose descendants explored the frontiers of the Yangtze to the east and south as well as other frontiers to the north and west, thereby creating "forks" that became the states of Qi, Yan, Jin, etc. The existence of feudalism allowed the pie to be divided among members of the dynastic family, lords, and key generals. At the same time, the existence of frontiers for centuries on all sides allowed these feudal states to revolve around the King of Zhou's gravity (for support and legitimacy) while turning their attention to conquest, colonization, and expansion outwards. The King of Zhou received tribute and recognition, whereas the feudal states expanded in a “non-zero-sum” manner. Everyone was a winner. It was no coincidence that Zhou became the longest lasting dynasty in all of Chinese history — longer than any dynasty that came after it.

Feudal States of Zhou Dynasty and Surrounding Frontiers. (Source: Philg88. Under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License)

Mongol Khanates

The Mongols under Genghis Khan started off with vast frontiers to conquer in the east, west, and south, including the plains of Northern China, the Silk Road passageways through Western Xia to Kara Khitai, the Khwarizm oasis in the Amu Darya to Central Asia, as well as the vast expanses of the Euroasian steppe from the Caspian Sea to the Dnieper River. Yet, by the time of Genghis’ grandsons, the frontiers had to a large extent been closed. To the west, Mamluks of Egypt stopped Mongol expansions to the Levant at Ain Jalut and subsequently again at Elbistan and Homs. To the east and south, Khublai Khan's navies succumbed to the kamikaze in their failed invasions of Japan, and also failed in their expeditions to Java.

As the Mongol Empire reached the natural limits of its expansion, its gravity imploded inward and it splintered into endless “zero-sum” infighting between khanates. To the west, the Ilkhanate and Golden Horde became mortal enemies and engaged in wars across the Caucasus Mountains; to the east, the House of Ögedei under Kaidu fought against Khublai Khan's Yuan dynasty for more than thirty years. The khanates fought among themselves for decades and eventually withered away in the ebb of history.

Depiction of Inter-Mongol Battle. (Source: Public Domain)

Synthesis and Relativity

Through the three sets of historical cases — competing ideological factions, intense national rivalries, and dynasties/khanates — we have seen how “zero-sum” rivalries fueled destruction, while seemingly “non-zero-sum” frontier expansion resulted in relative conflict avoidance, peace, and growth. In the latter two historical case sets, previous frontiers eventually became closed off or colonized, resulting in renewed infighting or rivalries that bred destruction.

Oftentimes, observations from history could find corollaries in the natural sciences. Now, let's go further down the rabbit hole and try to make some connections to relativity. We start with Theory of Special Relativity.

Special relativity supports the idea that physical laws are the same for inertial frame of reference, but may differ in non-inertial or accelerating frame of reference. The frame of reference makes a big difference. Special relativity also explains that, under different accelerations, time flows differently and objects may have measured length contractions or different lengths.

Measured Length Contraction (Source: Stigmatella aurantiaca. Under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License)

In a historical sense, one could argue that the definition of frontier had been highly relative to the frame of reference, and that for every side accelerating or making a frontier push, there was another side that saw things differently. Hence, what seemed to be “zero-sum” wasn't really so. For the Puritans, the New World represented a new frontier, whereas to the Native Americans it had nearly always been home. For post-Napoleonic France, Algiers had been a new frontier, but for the North Africans, it had been conquest, colonization, and assimilation. For the Zhou dynasty and Mongol Empire, all directions represented frontiers to expand, but for the assimilated tribes or conquered kingdoms, those had been different experiences.

Differing Frames of Reference (Source: Krea. Under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License)

We move next to the Theory of General Relativity, which explains gravity as a distortion of space; in other words, very massive objects with center of gravity would warp space-time. In history, the center of power had also produced different curvatures under different contexts. With generally available frontiers, as was in the case of early Zhou dynasty, the Zhou court's mass and "gravitational push” enabled various feudal states in orbit to obtain material support and cultural cohesion, while the court's defense needs could also determine a feudal state's path of frontier expansion. With closing frontiers, as was in the case of late Mongol Empire, due to the pull of the dynastic center and its related struggles, the "gravitation distortion" and collapse was inward, and internal infighting ensued.

The continued expansion of the universe is also generally relativistic. To avoid an eventual collapse inward, one needs to seek what Balaji would term “infinite frontier” that continues to expand outward opportunities for growth.

Conclusion

Looking forward, as new physical and digital frontiers are scouted, explored, and populated, whether in the seas, in space, or via the Internet, we should be cognizant of the following:

1 - Making sure that one side's frontier is not another side's loss, so that everyone and every side collectively can thrive, grow, and invigorate.

2 - Making note of the "gravitational” critical mass pull that could either fuel one's momentum or cause one to eventually collapse inward.

3 - Making attempts to create continuously expanding growth so that the frontier momentum does not abate.

This concludes our exploration into the rabbit hole. Sometimes, lessons into history and theories of nature could have connections! Thank you for reading!

Disclaimer: This post is purely academic in nature, and it does not constitute any formal political, scientific, legal, financial, social, or ethical advocacy. For earlier posts and musings, please visit whatifwhatif.substack.com.