Winds of Paradigm Change: From Early Christians, 1776ers, and Marxists to the Network State

A look at sample lessons that the network state movement could learn from the early Christians, the 1776ers, and the Marxists.

Introduction

Through a series of no-punches-withheld discussions, Balaji Srinivasan's The Network State explores how we have arrived at the world of the 2020s, where we may be headed next, and what we can do to create new futures characterized by the concepts of network unions, network archipelagos, and network states (these concepts are also explained more here). A network state is, in one sentence:

A highly aligned online community with a capacity for collective action that crowdfunds territory around the world and eventually gains diplomatic recognition from pre-existing states.

- Balaji Srinvasan, The Network State

The road from startup societies to network states hopes to give many an alternative paradigm out of domestic socio-political impasse, zero-sum global great power competitions, inefficient economic distributions, global mobility and regulatory roadblocks, ecological upheavals, and other major 21st century challenges.

In less than a year, a number of startup societies have sprouted and grown (visit here for a more comprehensive dashboard list of budding startup societies), and ones such as Build Republic, Afropolitan, and Plumia hold much promise for the future. Arguably, the budding network state movement can be paradigm changing in the decades to come. As nation state domestic politics continue to divide, global Cold War 2.0 tensions continue to rise, inequality gaps continue to widen, global mobility continue to be restricted, technological progress continue to be stifled by politicized regulation, and ecological environments continue to worsen, many more around the world will hope to embrace new paradigms and more effective structures that could solve pressing challenges. The network state movement will likely see major opportunities to grow, and likely along the way, face major obstacles and challenges.

In some sense, this trend is not new. By looking at the past, we can find other eras in which a major paradigm-shifting movement with a new vision for organizing people and societies inspired millions, built and sustained momentum, and eventually changed the course of history. In this essay, we will explore three such examples: the early Christians, the 1776ers, and the Marxists.

Like the network state architects and enthusiasts who often see Balaji's The Network State as their manifesto, the early Christians, the 1776ers, and the Marxists could each trace their beginnings from their own manifestos: the New Testament for early Christians, the Declaration of Independence for 1776ers, and the Communist Manifesto for Marxists. Despite holding vastly different in ideologies and beliefs, the Christians, the 1776ers, and the Marxists all grew in response to macro level upheavals in their era and weathered through challenges to survive, grow, thrive, and eventually become the pre-dominant paradigm and establishment for subsequent centuries. The essay will make an attempt to mine sample lessons from these three past paradigm-changing movements — and these are by no means exhaustive — in hopes of seeing what the network state movement could learn and adapt.

Early Christians, 1776ers, and Marxists (AI Generated Images)

Early Christians, 1776ers, and Marxists Unite!

Although the early Christians, the 1776ers, and the Marxists believed in fundamentally different ideologies about the way the world should work (and this essay is not an endorsement of any of these ideologies), they also encountered numerous situations and exhibited many characteristics that make them viable and interesting subjects of study for the network state movement in the 21st century. Let's dive in.

Macro Existing Order Under Fire

Decline. The early Christians experienced the Crisis of the 3rd Century, through which the existing “world order” of the time, defined earlier by Pax-Romana, witnessed fracture, tension, division, and decline. The Roman Empire of the Augustus and Hadrian days that established norms of governance, trade, and society could no longer hold things together: to the North, the empire could not guard an overly stretched but porous border teeming with incursions by various tribes; to the East, an aggressive Sassanid dynasty rose from the ashes of the Parthians, Rome's previous geopolitical competitor, and challenged Rome's hegemony in the Near East, a core strategic region of global trade at the time. Within Rome, divisions within political factions spelled intense civil conflict and civil war, for a period even fracturing the empire into three parts. Economically, the empire and its citizens also experienced sharp inflation, decreasing power of its currency, and widespread economic depression.

Sounds familiar? Many 21st century inhabitants of the Western world who are wary of domestic political conflict, culture wars, geopolitical tensions, inflation, immigration, and de-dollarization may nod in agreement.

Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire, Destruction (Public Domain)

Disconnect. Let's then look at the 1776ers. The 1776ers populated a new frontier (to use a Balajian concept) that manifested new ways of organization, interaction, activity, and thinking. Yet, they were governed by and regulated by Old World institutions under a monarchy that had defined the existing order for centuries. This disconnect, as exemplified by taxation without representation, led to widespread resentment and challenges.

Sounds familiar? Many 21st century digital nomads and techies would nod. To borrow a Balajian concept, the Internet has defined a new frontier that established new modes of engagement, economics, mobility, and value creation, and yet, people of the Internet are still in large part regulated by static frameworks defined by 20th century pre-digital norms.

Boston Tea Party (Public Domain)

Disruption. Finally, let's take a look at the Marxists. Early Marxists witnessed a period of intense technological disruption through which previously agrarian societies evolved into industrial ones. The old technological order vanished. The spinning wheel and steam engine made previous modes of production obsolete, altered the livelihoods of millions, and introduced new production lines that unleashed capitalist potential along with widening inequalities.

Sounds familiar? Many 21st century folks glued to ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, and other AI platforms may nod in unison.

Industrial Revolution and Power Loom Weaving (Public Domain)

“Global” Networks

To a large extent, the early Christians, 1776ers, and Marxists were all people of the network in a backdrop of authoritarian persecution, hegemonic establishment, and great power competition respectively.

The early Christian networks during the Roman Empire consisted of decentralized communities of followers dedicated to the teachings of Jesus Christ. These communities were spread “globally” from the Near East through Asia Minor to the Adriatic Coast, Italy, Africa, and the Atlantic (and even to the Sassanid Empire as well as to South of the Nile), and connections between nodes were made through letters, visits, and a shared understanding of beliefs and practices. In spite of persecutions by the Roman authorities, the Christian "global” network survived and grew.

Early Christian Community by Maarten de Vos (Public Domain)

The 1776ers established strong networks across the Thirteen Colonies in spite of hegemonic British rule. For example, Committees of Correspondence were set up along towns and counties to share ideas, offer mutual support, and establish coordination. The 1776er network also applied various means of communication, such as newspapers, pamphlets, and personal correspondence, to disseminate ideas and mobilize support among the colonial population. Despite the initial challenges they faced, these colonial networks helped to build a sense of unity and shared purpose from Massachusetts to Georgia.

The early Marxists set up an internationalist movement amid great power competition by the European states of the mid-to-late 19th century and the early 20th century. International communes and networks were established in multiple countries in Europe and the Americas to realize Marxist ideas of sharing resources and working together. Although many of these communes were often small and short-lived, facing numerous challenges such as internal conflict, limited resources, and government repression, these network nodes formed important parts of the broader socialist and labor movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Redefining the State

The Christians, 1776ers, and Marxists all completed paradigm shifts from the existing status quo to establish a new form of state and charter new social contracts.

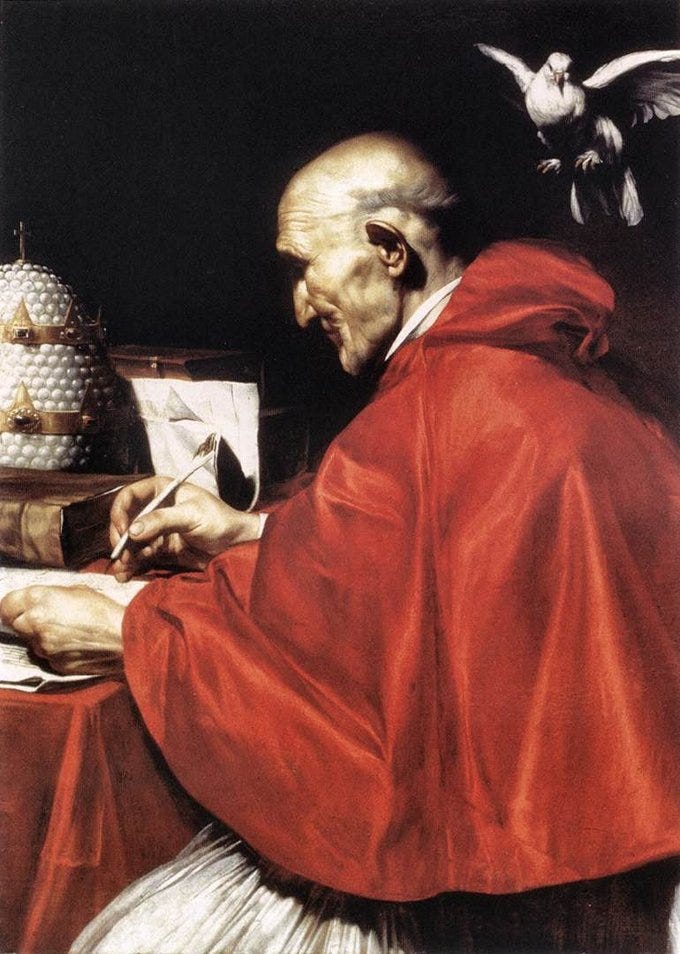

Church State. Most of the dominant states in Antiquity prior to Christendom were polytheistic kingdoms, republics, and empires. The Christians then ushered in a new era, by introducing the monotheistic church state as a pre-dominant form of governance and civil structure. One could argue that earlier Jewish kingdoms were also examples of monotheistic states, but the Christian movement arguably had greater historical impact on establishment. As Christianity became the official religion in the Roman Empire of Late Antiquity, replacing the paganism that defined status quo for centuries, the Church, its bishops, and the papacy grew in importance, and even the late Roman emperors often played a central role in the affairs of the Church. As the Western Roman Empire fell, the Church and the state became even more entwined, with the Pope — becoming the ultimate authority in matters of faith and morals — assuming immense political and religious power simultaneously, including the power to excommunicate individuals and even kings (see Frederick II). The church state became the establishment, and for the masses, it held the stamp for eternal salvation.

Pope Gregory the Great (Public Domain)

Representative Republic State. Most of the dominant states following the Seven Years’ War were absolute monarchies. The 1776ers then launched a new era, by introducing the representative republic state in which popular sovereignty, instead of monarchial sovereignty, became the guiding principle. One could argue that earlier Greco-Roman city states were also examples of republics, but the American Revolutionary movement arguably had greater historical impact. The newly formed constitutional republic of the United States inspired more republican revolutions in Latin America and in France, leading to an era in which modern republics would outnumber monarchies. The representative republic nation state became the establishment, and for the masses, it would hold the social contract between citizenry and elected governance.

U.S. Constitution (Public Domain)

Communist Ideological State. Most of the dominant European states around the turn of the 20th century were involved in intense Bismarckian nationalist great power competition. The Marxists then created an ideological bloc that was internationalist in nature. The former Soviet Union was an internationalist entity that saw itself as a champion of the Comintern World Congress and the international Communist cause. The Soviet Union became heavily influential in architecting the Communist bloc of countries, which included countries in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and East Asia. The communist ideological state became the establishment in much of the world the 20th century, and for the masses in the Communist bloc, it would hold ultimate power over planning, rationing, and distribution.

Second Congress of the Comintern (Public Domain)

Sample of Lessons Learned

In the next part, we will explore and mine sample lessons that the network state movement could learn from the movements launched by the early Christians, the 1776ers, and the Marxists — in terms of survival, growth, and mass adoption.

Core Early "Missionaries”

The early Christians, 1776ers, and Marxists all attracted to-die-for zeal from early “OG”s. Each movement grew from core groups of believers who made it their lifelong mission to grow and sustain momentum, even in the face of persecution. A strong, highly engaged core group was often needed before scaling to the thousands and millions.

Despite facing many challenges, including persecution from both the Roman authorities and from other religious groups, the early Christian missionaries persisted in their efforts to spread the gospel throughout the Mediterranean. Through their tireless work, they established the foundations of the Christian Church and laid the groundwork for its growth and expansion in the centuries to come. The missionaries also served as spiritual leaders, providing guidance and support to the new converts and helping to build a sense of unity among the members of the early Christian communities.

Early core groups played a crucial role in growing and sustaining the American Revolution. Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and John Hancock were among a group of die-hards who formed the Sons of Liberty, which emerged in the early years of the revolutionary movement in response to increasing British attempts to exert control over the American colonies. This group of influential leaders, merchants, and ordinary citizens helped to galvanize public opinion and build support for the revolutionary cause. Through their political activism, resistance, and organization, this early society of core believers laid groundwork for the eventual success of the American Revolution.

Early Marxists relied on the zeal of early zealot groups and unions dedicated to the struggles of the working class. The First International, also known as the International Workingmen's Association, was founded in London in 1864 and became the first international organization of the socialist and labor movements. It brought together workers from various countries, including England, France, and Germany, to coordinate their efforts and struggles against the capitalist system. In the following years, Marxist parties and labor unions emerged in more countries, and these groups dedicated to spreading Marxist ideas as well as organizing workers for a political and economic new order.

Near Universal Appeal

To scale beyond early communities, and to allow these core early groups to lead as well as facilitate more broader connections, the Christians, 1776ers, and Marxists all aimed for near universal appeal in their core messages and values. These movements didn't cater to only special interests or niches, but instead to millions looking for hope, enlightenment, and justice. The "Chariot Clubs,” “Frontier Wig Clubs,” and “Spinning Machine Clubs” all faded, while the church state, representative republican state, and communist state became mainstays in history.

The early Christian message of hope, salvation, and forgiveness resonated with the masses of the Roman Empire, especially among those who were marginalized, such as slaves and women. The Christian message of equality, which stated that all people were equal in the eyes of God, was a radical and appealing idea for those who felt oppressed by the hierarchical structure of pagan Roman society. Additionally, the promise of eternal life offered comfort and reassurance to those facing poverty, disease, and death, especially as the Roman Empire crumbled. Communities fostered by early Christian gatherings provided support and a sense of belonging to those who were often excluded from broader society. These factors, combined with the charisma and conviction of early Christian leaders, helped the early Christian message to spread and gain a large following.

The American Revolution was infused with Enlightenment ideas of equality and the natural rights of man. These ideas resonated with the masses, because they spoke to a desire for fairness and justice. Furthermore, the idea of a "government by the people, for the people" was appealing to the masses of colonials who felt that their interests were no longer represented or heard.

The Marxists appealed to masses while addressing the widespread feelings of economic exploitation and poverty among the working class. At a time of great economic, technological, and social upheaval, Marxists spoke to the grievances and aspirations of millions around the world. Early communism was based also on the idea of international solidarity and the belief that the struggles of workers around the world were interconnected. These ideas were then in turn often associated with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles, which helped to attract supporters outside of Europe and to build a broader global base of support for the movement.

Powerful Allied Support

Despite having enthusiastic early core groups and potential for mass appeal, movements could find themselves facing extreme adversity — especially in the hands of establishments that may see them as threats to the existing status quo — and facing the prospect of being stifled in their infancy. The early Christians, 1776ers, and Marxists survived and succeeded in part because they latched onto more powerful support and recognition beyond their core.

For the early Christians, one of the most significant examples of this support came from Emperor Constantine the Great, who in the early 4th century declared himself a Christian. This provided a great deal of protection and support for Christians, and allowed the religion to flourish and grow. Another example of Roman support for Christianity came from wealthy and influential individuals, such as patricians and senators, who saw the religion as a way to align themselves with the growing power and influence of the Christian community. They provided financial support for the construction of churches and the establishment of Christian institutions, and used their influence to advocate for the religion and protect Christians from persecution.

The 1776ers also realized a need for external support in the face of significant challenges. The American revolutionaries found key support in the form of France. In addition to military aid, the French also provided financial support to the American cause: the French government lent money to the Continental Congress, helping to keep the newly founded American army and government functioning during a time when the independence war effort was putting a severe strain on their resources.

The Marxists soon realized that urban industrial workers were not enough, and that to sustain bigger momentum, they needed to inspire and mobilize bigger segments. The Bolsheviks were able to find such mobilization among the rural Russian peasantry. One of the key factors in the Bolsheviks' support among farmers was their policy of land redistribution. The Bolsheviks nationalized large estates and redistributed land to the peasantry, giving them control over their own land for the first time. This policy was particularly popular among farmers who had previously been oppressed by wealthy landowners and faced significant hardships under the feudal system. The Bolsheviks sought to educate and mobilize the peasantry, using propaganda and political education to build support for their regime. Through these efforts, the Bolsheviks were able to build a base of support among the vast rural population and eventually drive a revolution.

Conclusion

The above list of inspirations are by no means exhaustive. To build, sustain, grow, and scale, mass paradigm-changing movements in history had enlisted core groups of enthusiastic “missionaries,” communicated near universal appeal in messaging, and found powerful allied support through recognition by influential power brokers and more like-minded groups. As the network state movement continues to grow, it could also try to gain momentum by engaging core startup society believers who co-lead community building initiatives, co-build key assets, and help refine key architecture or follow up proposals; by delivering value propositions that appeal to a global audience inclusive of the East, West, and South; and by collaborating with other forward thinking institutions, societies, and even nations.

Network State Map (AI Generated Image)

This is essay 1 of 4 essays for The Network State (TNS) Creators Cohort #3 (by 1729 Writers). 1729 Writers is a group that writes to reflect on the network state movement, AI, trans-humanism, and other techno-socio topics.

Disclaimer: This post is academic in nature, and it does not constitute any formal political, scientific, legal, financial, social, religious, or ethical advocacy. For earlier posts and musings, please visit whatifwhatif.substack.com.

We have a tool the movements of the past did not. Collective Intelligence.

We can use it to govern like this:

https://joshketry.substack.com/p/direct-democracy-is-the-answer-lets